Large-Scale Long-Tailed Recognition in an Open World

This is a blog post for Large-Scale Long-Tailed Recognition in an Open World, a CVPR 19 paper.

Existing Computer Vision Setting v.s. Real-World Scenario

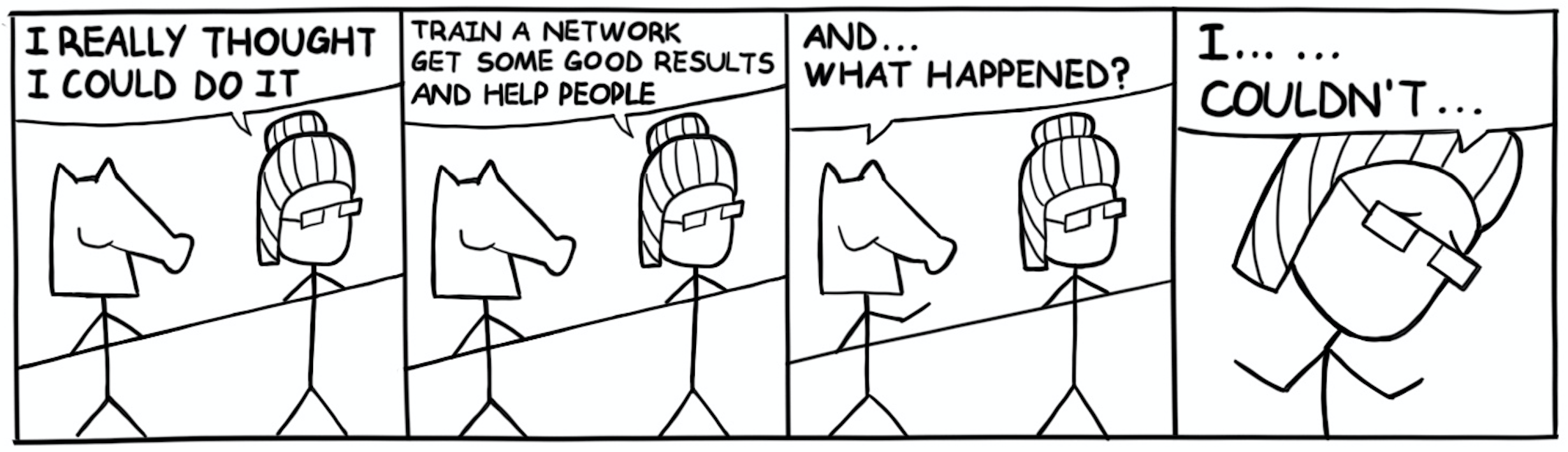

One day, an ecologist came to us. He wanted to use modern computer vision techniques to perform automatic animal identification in his wildlife camera trap image datasets. We were so confident because it sounded just like a basic image classification problem. However, we failed. The dataset he provided was extremely long-tailed and open-ended. As usual, when we did not have enough training data, we asked if it was possible to provide more data for the tail classes and just ignore the open classes that might appear in the testing dataset. Unfortunately, collecting more data was not the option. It could take an extremely long time for these ecologists to take photos of rare and secluded animals in the wild. For some endangered animals, they even had to wait for years for one single shot. At the same time, new animal species kept coming in, and old animal species kept leaving. The total class number was never fixed in such a dynamic system. Moreover, the identification of rare and new animals has more conservational values than abundant animals. If we could only do well on the abundant classes, the method would never be practically usable. We tried all possible methods we could think of (data augmentation, sampling techniques, few-shot learning, imbalanced classification, etc.); but none of the existing methods could handle abundant classes, scarce classes and open classes at the same time.

There exists a considerable gap between the existing computer vision setting and the real-world scenario.

Since then, we have been thinking, what is the biggest reason for this gap between existing computer vision methods and real-world scenarios? Similar situations don’t just happen in wildlife image data, they happen over and over again in real-world scenarios (both in the industry and in the academia). If convolutional neural networks can classify images from the massive ImageNet dataset so well, why image classification is still an unsolved problem in an open world? Almost every task (e.g. few-shot learning and open set recognition) proposed in visual recognition field has successful approaches, but it seems that no one has tried to see those problems as a whole. When it comes to real-world applications, classification tasks (either for head classes or for tail classes) sometimes do not just come alone. Therefore, we think that the gap may come from the problem setting of visual recognition itself.

Open Long-Tailed Recognition (OLTR)

In existing visual recognition setting, the training data and testing data are both balanced under a closed-world setting, e.g. the ImageNet dataset. However, this setting is not a good proxy of the real-world scenario. For example, it is never possible for ecologists to gather balanced wildlife datasets because animal distribution is imbalanced. Similarly, people are bothered by the imbalanced and open-ended distribution from all sorts of datasets: street signs, fashion brands, faces, weather conditions, street conditions, etc. To faithfully reflect these aspects, we formally study “Open Long-Tailed Recognition” (OLTR) arising in natural data settings. A practical system shall be able to classify among a few common and many rare categories, to generalize the concept of a single category from only a few known instances, and to acknowledge novelty upon an instance of a never seen category. We define OLTR as learning from long-tail and open-end distributed data and evaluating the classification accuracy over a balanced test set which includes head, tail, and open classes in a continuous spectrum (Fig. 2).

While OLTR has not been defined in the literature, there are three closely related tasks which are often studied in isolation: imbalanced classification, few-shot learning, and open-set recognition. Fig. 3 summarizes their differences. The newly proposed Open Long-Tailed Recognition (OLTR) serves as a more comprehensive and more realistic touchstone for evaluating visual recognition systems.

The Importance of Attention & Memory

We propose to map an image to a feature space such that visual concepts can easily relate to each other based on a learned metric that respects the closed-world classification while acknowledging the novelty of the open world. Our proposed dynamic meta-embedding combines a direct image feature and an associated memory feature, with the feature norm indicating the familiarity to known classes, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Firstly, we obtain a visual memory by aggregating the knowledge from both head and tail classes. Then the visual concepts stored in the memory are infused back as associated memory feature to enhance the original direct feature. It can be understood as using induced knowledge (i.e. memory feature) to assist the direct observation (i.e. direct feature). We further learn a concept selector to control the amount and type of memory feature to be infused. Since head classes already have an abundant direct observation, only a small amount of memory feature is infused for them. On the contrary, tail classes suffer from scarce observation, the associated visual concepts in memory feature are extremely beneficial. Finally, we calibrate the confidence of open classes by calculating their reachability to the obtained visual memory.

Across-the-board Improvements

As demonstrated in Fig. 5, our approach provides comprehensive treatment to all the many/medium/few-shot classes as well as the open classes, achieving substantial improvements on all aspects.

Visualization of Learning Dynamics

Here we inspect the visual concepts that memory feature has infused by visualizing its top activating neurons as shown in Fig. 6. Specifically, for each input image, we identify its top-3 transferred neurons in memory feature. And each neuron is visualized by a collection of highest activated patches over the whole training set. For example, to classify the top left image which belongs to a tail class “cock”, our approach has learned to transfer visual concepts that represent “bird head”, “round shape” and “dotted texture” respectively. After feature infusion, the dynamic meta-embedding becomes more informative and discriminative.

Back to the Real World Now we go back to the real jungle and apply our proposed approach to the wildlife data came with the ecologist mentioned in the first section. Fortunately, our new framework achieves a substantial improvement on scarce classes without a sacrifice of the abundant classes. More specifically, we obtain around 40% performance gains (from 25% to 66%) on classes with less than 40 images. And we also obtain over 15% performance gains for open class detection.

We believe computational methods developed under open long-tailed recognition setting can ultimately satisfy the needs of natural-distributed datasets. In summary, Open Long-Tailed Recognition (OLTR) serves as a more comprehensive and more realistic touchstone for evaluating visual recognition systems, which can be further extended into detection, segmentation and reinforcement learning.

Acknowledgements: We thank all co-authors of the paper “Large-Scale Long-Tailed Recognition in an Open World” for their contributions and discussions in preparing this blog. The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely of the authors of this paper.

This blog post is based on the following paper which will be presented at IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019) as an oral presentation:

- Large-Scale Long-Tailed Recognition in an Open World Ziwei Liu, Zhongqi Miao, Xiaohang Zhan, Jiayun Wang, Boqing Gong, Stella X. Yu Paper, Project Page, Dataset, Code & Model

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: